Lisa Monhoff, at that time the archivist at the Charles M. Schulz Museum, called to warn me that I

probably would hear from this fellow, an account manager at KNTV. Sure enough, within 5

minutes I received the following e-mail:

Hi there:

Some colleagues of mine here at NBC are trying to remember the name of the Peanuts character who

walked around with a cloud over his head (not Pigpen with the dust cloud).

I called the Peanuts Research Center/Museum, and they couldn't give me the answer.

But they gave me your contact information.

Can you help answer this question?

Many thanks.

Let us be absolutely clear on one point: Lisa most certainly did answer his question,

and in fact she gave him the same information I supplied. She was not amused when I forwarded

a copy of my response, particularly since this gentleman apparently took my word over

hers ... despite the fact that we both said the same thing, and she said it first.

Sexism ... becomes tiresome.

More to the point, though, this illustrates a phenomenon that I've confronted many

times over the years, in my unofficial capacity as cheerful, tireless researcher

of All Things Peanuts for people resourceful enough to contact me: the occasional refusal

to accept the response of an authoritative source, if it conflicts with one's (invariably imperfect) memory.

I mean, really, if you have a Peanuts-related question, why would you not believe an

answer supplied by the Charles M. Schulz Museum?

People can be funny. They get these ideas into their heads, and it's darn near impossible

to shake 'em loose. Doesn't matter how hard you try, how persuasively you present the dissenting

viewpoint, or the possible multitude of facts to support the actual, correct answer.

They'll continue to believe themselves correct despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

And, in fairness, the Internet has worsened this situation. Time was, a bad idea or blindingly

incorrect fact got no further than its sole point of publication. These days, such things travel

the world -- via the Web -- and propagate like fruit flies. Careless research doesn't help; a

credulous scholar easily could find several dozen sources for the same bad information ... not

realizing that every one of them merely repeated the original error, thanks to those always-busy

'bots that scoop up and distribute everything on the Web.

This, by the way, is my primary objection to a site such as Wikipedia: It's not authenticated.

Yes, some of the listings are written by experts in their field, who care deeply about accuracy.

On the other hand, many listings are contributed by well-meaning fans, who aren't always as accurate

as they'd like to believe.

And there's nothing more aggravating, when I deal with a questioner, than somebody who argues

with my response and cites a Wikipedia entry -- or something similar -- as evidence of my supposed "ignorance."

The world of Peanuts, like any other specialized field, has its share of rumors, misunderstandings

and just plain hoaxes (not too many of the latter, fortunately). Some of them predate the Internet;

others have been created and spread by the Internet. I've fielded some of them repeatedly;

so have Lisa and other highly visible Peanuts authorities such as friend and fellow PCC member Scott McGuire,

who gets the attention thanks to his highly informative Peanuts TV, film, video and book-oriented Web site.

(Check it out here.)

The note above prompted me to check in with Lisa and Scott, to gather the best -- and most

irritatingly frequent -- Peanuts rumors, misunderstandings and hoaxes. You may have seen one

or more of these. You may even believe some ... although I hope your opinion changes by the end of this article.

Mostly, though, I hope you don't spread them. The Internet becomes a scarier place when bad

information crowds out good information. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to help

stem the flow of falsehood. Stand up for the integrity of Charles Schulz's vision!

So then: to the issues at hand.

Misconceptions

Charlie Brown is bald.

This one circulates a lot, although I've rarely responded to a direct question from

somebody wanting to know one way or the other. It's just a common and patently false assumption,

based on the way Charlie Brown is drawn. He's most certainly not bald; he's just very, very, very,

very blond ... what my parents would have called a tow-head (a phrase, come to think of it,

that I don't hear much any more). Charlie Brown's hair is so fine that it simply doesn't show up

that clearly, hence we see only the occasional strand.

Confirmation for this information was given by no less than Charles Schulz himself, during a December 18,

1990, interview with Terry Gross on National Public Radio's Fresh Air:

I don't think of it as not having hair. I think of it as being hair that is so blond that ... it's

not seen very clearly, that's all.

He repeated this information a few years later, during an interview on NPR's Morning Edition:

Well, he's got hair, it's just so light you don't notice it. I always resent it when people say he's

bald. He's not bald. The old character Henry was bald. But Charlie Brown has a little hair. His dad is a barber,

as my dad was. He must have had hair someplace up there.

The issue became a bit confused in the wake of the 1975 TV special, You're a Good Sport, Charlie Brown,

when upon winning the motocross competition ol' Chuck received a prize of ... five free haircuts.

"But my dad's a barber," Charlie Brown protested, "and besides, I don't have much hair to cut!"

No problem there; it simply means that Charlie Brown's hair is mostly short, crew-cut fashion,

except for a few stray long hairs, and we always see the latter.

The Great Pumpkin lives!

Scott has gotten this question more than the rest of us, because of his Web site's focus.

For some rather peculiar reason, lots of people believe that when It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown

first showed on TV -- but only the first time -- it included a scene that actually revealed the Great Pumpkin

(sometimes thought to have been peering in a window of Linus and Lucy's house). As this rumor goes, the scene

in question was deleted after that one and only airing.

Oh, puh-leaze!

No doubt such folks misremember the fact that Linus does indeed see a shadowy figure rising from the pumpkin

patch ... but, as most of us know, that "mysterious" figure turns out to be Snoopy.

I'm sure no avid Peanuts fan would be suckered by this one; we all know that the Great Pumpkin,

like the Little Red-Haired Girl, is one of the imaginary icons that Schulz made a point of never showing

in his strip. Given the degree to which Schulz was involved in that TV special -- only the third one

created -- he most certainly never would have okayed actually revealing the Great Pumpkin, and nobody

could have made such a decision against his approval.

Besides ... what in the world would the Great Pumpkin have looked like? I mean, seriously!

And yet people swear that they saw just such a scene, that one time, and they'll refuse to take our

steadfast word that they're mistaken.

Go figure.

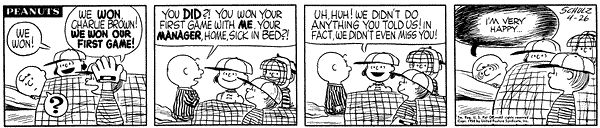

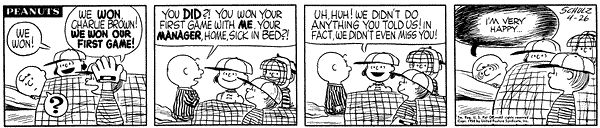

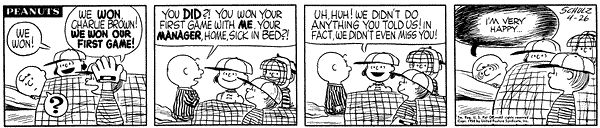

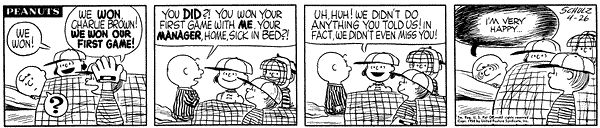

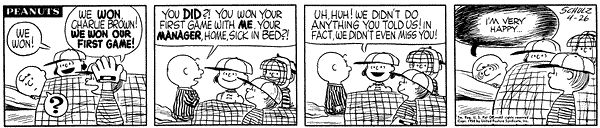

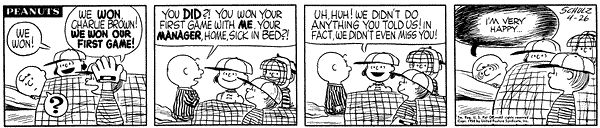

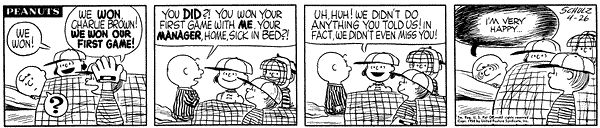

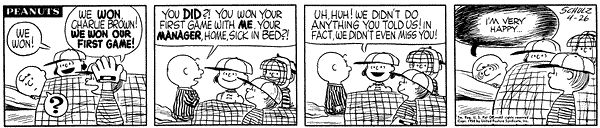

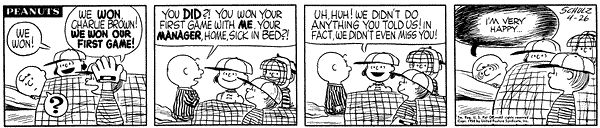

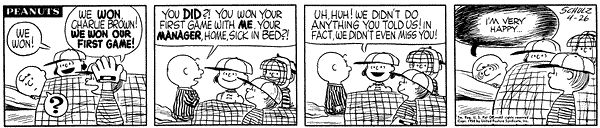

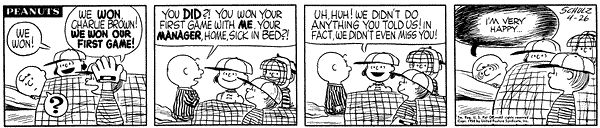

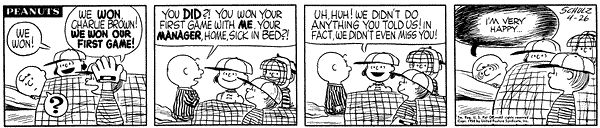

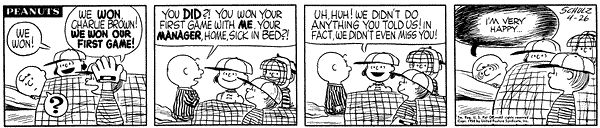

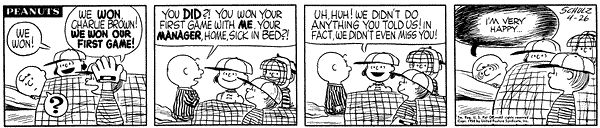

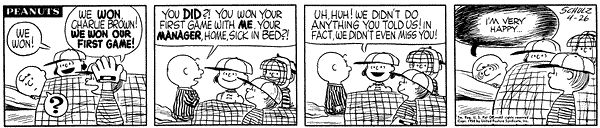

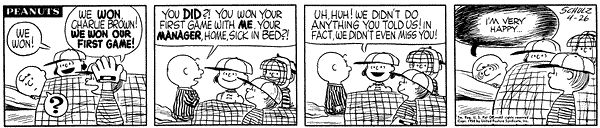

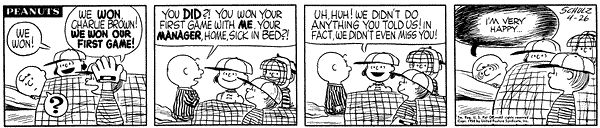

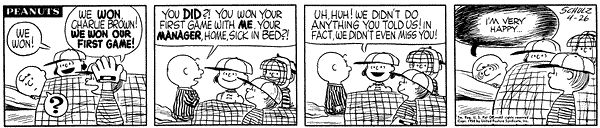

April 26, 1958

Charlie Brown's baseball team never won a game.

Folks take for granted -- mainly because Charlie Brown himself reinforces the notion -- that his

baseball team remained win-less every season. While ample evidence exists that things go pretty badly

("We always seem to lose the first game of the season and the last game of the season ... and all the stupid

games in between!"), in point of fact ol' Chuck's team has won a few.

A few notable newspaper strip examples:

4/26/58: Just prior to the first game of the season, Charlie Brown winds up home in bed, feeling sick.

Lucy leads the gang into his bedroom later that day, and triumphantly proclaims, "We didn't do anything

you told us! In fact, we didn't even miss you!" And, as a result, the team wins the game.

6/10/65: Having (as usual) been shipped off to camp for the summer, Charlie Brown receives a letter

from Linus, which says, among other things, "I suppose you are worried about your baseball team. Well, don't

worry ... we're doing fine ... in fact, yesterday we won the first game we've won all season!"

8/5/66: After getting hit on the head with a line drive -- a few days earlier, on 8/2 -- and being forced

to spend the rest of the game on the bench, ol' Chuck's team triumphs again. "We won, Charlie Brown!" Lucy shouts.

"We won the game!"

8/16/68: Thrown into a tizzy when he notices the Little Red-Haired Girl watching the game from the stands,

Charlie Brown gets the shakes so badly that he cannot pitch the game. Relief pitcher Linus takes over, and the

team wins again.

4/22-23/69: When Peppermint Patty and Franklin both finds themselves unable to field an entire team,

they reluctantly tell Charlie Brown that his team has won by forfeit ... both times. Alas, the two-game

winning streak ends the next day, when the other team (we don't know whose) shows up.

4/9/73: When the opposing team has trouble pitching to Rerun because of his small size, the little guy

walks in the winning run, and Linus triumphantly shouts, "We won! We won, Charlie Brown!" Alas, the Little League

president eventually takes the game away because of gambling: Rerun, ever the loyal player, bet Snoopy

a nickel that his team would win.

You may have noticed, by now, that most of these victories took place in Charlie Brown's absence ... but it's

equally untrue to assume that he never personally brought his own team to victory.

Consider, most famously...

3/30/93: With Royanne Hobbs pitching against him, Charlie Brown hits his first-ever home run (in the ninth inning)

and wins the game.

6/29/93: Once again facing Royanne Hobbs, Charlie Brown hits another home run, and brings his team to victory again.

It's true that both these home runs later prove to be bittersweet victories ... but ol' Chuck really doesn't care!

May 23, 1954

Adults never appeared in the strip.

People who still believe this one just aren't reading the strip very carefully, and I hope that Fantagraphics'

Complete Peanuts anthologies may, finally, banish this misconception once and for all.

And, as you'll also discover, dealing with this question also takes care of a second, related mistaken

assumption: Adults in Peanuts have spoken actual words. Believing otherwise is a result of the animated TV

specials, where adults mostly are limited to those hilarious waah-waah outbursts. (But not exclusively,

so let's not start that rumor, either. Adults do speak actual dialogue in some of the animated shows.)

September 18, 1966

Charlie Brown's mother makes an off-camera appearance in the 11/7/50 strip, when she calls him by name.

Similarly, Charlie Brown's father makes an off-camera appearance in the 6/20/93 Sunday strip, when he

plays with Snoopy and talks to him in no fewer than eight word-balloons. So we also have irrefutable proof

that ol' Chuck is growing up in a happy, two-parent household.

In the 10/17/54 Sunday strip, Charlie Brown, attempting to attain the same level of security as Linus,

hustles into a store to purchase one yard of outing flannel ("And DONT LAUGH!!," he tells the clerk).

Look closely, and you'll see the clerk's left hand, complete with wedding band.

The best early use of almost-wholly-there adults, however, comes in four consecutive Sunday strips involving

Lucy's participation in a golf tournament, with Charlie Brown at her side as sort of a one-man cheering squad.

Numerous adults appear in close-up, from the waist down, in a few panels. In other panels, you can see groups

of adults in the cheering gallery, although their faces remain obscured.

Schulz also used Snoopy in his infantry beagle mode to commemorate Memorial Day and Veterans Day.

The 5/31/98 Sunday strip, a huge single panel, placed the comic strip beagle against a background photograph

of soldiers designed to honor the anniversary of D-Day. Later the same year, Schulz went one better than his

usual acknowledgment of war-era cartoonist Bill Mauldin, in whose honor Snoopy usually quaffs a root beer

each November 11. In the 11/11/98 daily strip, Snoopy actually meets Mauldin's Willie and Joe, the comic

strip soldiers who conveyed the weary loneliness of WWII life for an entire generation. They're even drawn

in Mauldin's style.

So: Plenty of adults. (Back in the early days, anyway.)

Joe Btfsplk

The Peanuts character who walked around with a cloud over his head ... but who isn't Pigpen.

Yes, from the letter above. (What, you thought I wouldn't tell you?)

This is a funny one, which has been gathering steam for the past several years ... funny in the sense

that I can't imagine why, how or where the rumor could have started.

For the record, then, there's no such character in Peanuts.

It's a persistent rumor, but wholly unfounded. I suspect bad memory: Folks are conflating Pig Pen -- with

his ubiquitous dust cloud -- with an actual character from Al Capp's Li'l Abner, who walked around with a

constant raincloud over his head. That character's name was Joe Btfsplk, and you can read about him

here.

You'll also note the few panels above, taken from Li'l Abner, which show this individual. I hope you'll

agree that he doesn't look a thing like any character who'd appear in Peanuts!

Charles Schulz didn't draw all the Peanuts strips, or had helpers/associates/background artists/etc.

Okay, this one's just insulting.

And completely false.

Of all the thoughtless and silly questions that sometimes pop up, this has to be the worst. How can

you examine any single Peanuts strip and not know, without question, that they always were rendered by the same hand?

For the record, Charles Schulz was -- and always was -- the only person to draw, write and

letter his beloved newspaper comic strip. While it is true that other daily strips have been (are) drawn

and/or written by consortiums overseen by the strip's creator, this never was the case with Peanuts.

So Schulz gave us a total of 17,897 Peanuts newspaper strips: 15,391 daily strips and 2,506 Sundays.

This takes into account leap years, the fact that Sunday strips did not begin until January 1952, and the

single vacation that he took, from November 27 through December 31, 1997 (inclusive).

That already impressive number does not include the hundreds of Peanuts spot panels Schulz also

did for gift books such as Happiness is a Warm Puppy, or his numerous illustrations for magazine

covers and interior articles. He kept busy.

To a degree, the belief that other hands became involved in the newspaper strip has been enhanced by

a few recent interviews given by comic artist Al Plastino, who claims -- in Alter Ego #59, for example -- that

he did Snoopy for a year and a half, in case Charles Schulz died after heart bypass surgery. Several examples

of Plastino's potential Peanuts strips have accompanied these interviews, but it's important to realize

that none of them ever was used in an official capacity.

Incidentally, Plastino's involvement wasn't a function of Schulz's health; Plastino actually was

brought in during a time when Schulz and his syndicate were arguing over contract details, and some

syndicate wonk thought he might gain better leverage if he, um, suggested that they could easily hire

somebody else to produce the strip. (Can you imagine?) Fortunately, saner heads prevailed, and the syndicate

managed to keep Schulz happy ... and that was the end of Plastino's potential involvement with Peanuts.

It is true, on the other hand, that several other unsung individuals handled the writing and artwork

chores when the Peanuts gang appeared in Dell and Gold Key comic books during the late 1950s and early 1960s.

For full details,

check out this article.

Schulz always made it plain that the newspaper strip would retire with him, and it did.

(And for the record, the strips still appearing in newspapers are older reprints ... not new

strips done by somebody else!)

Now that he is no longer with us, nobody else will take over. And that is absolutely as it should be.

March 13, 1978

Peppermint Patty and Marcie are gay

First of all, take a deep breath, and proceed with an open mind.

Readers are absolutely entitled to draw every possible comfort from their artform of choice,

whether books, plays, movies or newspaper comic strips. It is not my intention to puncture any

joyous bubbles; the commentary here is aimed mostly at the more militant individuals who insist

on taking the "truth" of this relationship for granted.

People can believe what they want ... but it's important to recognize that Schulz intended

no such reading of Peppermint Patty and Marcie ... or, for that matter, any other character in the Peanuts world.

Consider this portion of Gary Groth's lengthy 1997 interview with Schulz, reprinted in the

book Charles M. Schulz Conversations:

Groth: You skirt sexuality per se and deal with a much more romanticized or idealized version of love:

Charlie Brown and the red-haired girl and his unrequited love for her, Peppermint Patty's interest in

Charlie Brown is oblique and touching, Lucy's unrequited love for Schroeder, etc., but you don't deal

directly with sexuality. Since the strip is one of the most personal ever done, and sexuality is such

an important part of one's life, I was wondering if you ever felt like you wanted to do that but couldn't,

because of the newspaper strip format and the restrictions of the newspaper audience.

Schulz: Well, in the first place, these are just little kids. That really puts a lid on it right there.

To Schulz, then, this was a non-issue.

Those who choose to read a gay relationship between Peppermint Patty and Marcie will point to the former's

butch behavior, and the latter's fondness for calling her friend Sir. But Peppermint Patty was designed, when

she debuted in the 1960s, as what then was known as a sports-oriented tomboy ... and there's a chasm between

tomboy and butch. And Marcie repeatedly said Sir because she mixed up her pronouns -- like Sally mangled the English

language -- and (later) because it annoyed Peppermint Patty ... and Marcie knew it. (And also because it was funny,

and Schulz knew it.)

July 21, 1979

Perhaps more crucial to this argument, as Groth mentioned above, is the fact that both Peppermint Patty and Marcie

have competitive crushes on Charlie Brown. Both dream of kissing him. Both have done so.

August 18, 1982

In the second Peanuts stage play, Snoopy!, an entire song -- "Poor Sweet Baby" -- was constructed around

Peppermint Patty's love for Charlie Brown.

May 28, 1973

For what it's worth, Peppermint Patty also dated Pig Pen briefly, in early 1980; they attended a dance together,

and Peppermint Patty came home quite smitten. But it didn't last, and she sooned resumed pining for Charlie Brown.

So, by all means, believe what you so desire ... but if you like the thought of Peppermint Patty and Marcie

being a couple, the newspaper strip evidence simply doesn't support that theory.

Hoaxes and pernicious fakes

The Snoopy IRS strip

No less a journalist than financial columnist Stephen Moore, writing for National Review Online, began

an April 15, 2003, column with the following paragraph:

Many years ago I framed a classic Peanuts cartoon on the wall of my office. It shows Snoopy sitting

on top of his dog house pecking away at his typewriter. The message he writes is,

Dear IRS: Please take me off your mailing list!

Only one problem, Steve: There's no such classic Peanuts strip!

The, ah, anomaly in question began life as Charles Schulz's June 19, 1997, Peanuts cartoon,

with Snoopy typing out the latest exploits of Andy and Olaf. Somebody -- possibly even a legitimate

editorial cartoonist -- re-lettered the strip so that Snoopy is typing, "Dear IRS, I am writing to you

to cancel my subscription. Please remove my name from your mailing list."

At the time, and in whatever original publication produced this item -- if it was, indeed, a legitimate

source -- Schulz may have been thanked and credited, as is standard with editorial cartoons. At this point,

though, that important little detail is long behind us.

The new words aren't even a close approximation of Schulz's distinctive lettering style. Despite this,

the legend has become famous enough that I frequently get requests from people who want to know which book

contains this strip.

(And no, I've no intention of reprinting the bogus strip here, because I don't wish to help it propogate further.)

Chances are, we'll never eradicate this menace now. But it won't be for lack of trying...

Charlie Brown, archery cheater

Same question, different particulars: People want to know where they can find the "hilarious strip" that

shows Charlie Brown shooting arrows into a fence; he then draws circles around one of the buried arrows

so that it appears as though he has achieved a perfect bull's-eye.

Same answer: No such strip exists.

When the print version of this article debuted in the Summer 2007 issue of the quarterly Peanuts Collector

Club newsletter, I mentioned at the time that this hoax was a little harder to fathom, because we never had seen

a faked strip that might explain why people keep remembering it.

It's true that Charlie Brown was quite the scamp in the strip's early years, displaying characteristics

we'd more likely expect from Dennis the Menace or Calvin, of Calvin & Hobbes. We wouldn't be surprised to see

either of those characters pull such a stunt ... although, as far as we've been able to determine, they never did.

Federal Trade Commission Chairman Timothy J. Muris referenced this anomaly, in a speech he gave June 11, 2002,

on the FTC's new privacy agenda (and noted in a subsequent press release):

In concluding his remarks, the Chairman described one of his "favorite Peanuts cartoons," in which Charlie Brown

first shoots an arrow at a fence and then draws a target around it, ensuring he gets a bull's-eye.

"It might have worked for Charlie Brown, but not for us," Muris said, regarding implementation of the FTC's

Privacy Agenda goals. "We have our targets in place. We are sending out many arrows. Our law enforcement and

related initiatives indicate that our aim is darned good."

So ... what are Muris and the others remembering?

Thanks to PCC member Michael Ingrassia, we now have an answer.

A syndicated comic panel called Brother Juniper featured that gag, and it also became

the cover of one of the pocket book reprints of Brother Juniper cartoons. As with Pig Pen and Joe Btfsplk, it

seems that folks are conflating two different characters. It almost makes sense, since Brother Juniper was

drawn in a way that suggests he didn't have much hair, as people frequently assume is the case with

Charlie Brown (see above).

You can find the cover for Brother Juniper Strikes Again by Justin McCarthy

right here.

"All you need is love ... but a little chocolate now and then doesn't hurt."

The quote above, which has become incredibly pervasive -- turning up on samplers, posters and countless versions of desktop art -- most frequently

is attributed to Schulz, and sometimes to Lucy. Such claims notwithstanding, Schulz never said any such thing, nor did any character in any Peanuts

strip say anything remotely approaching this phrase. (On top of which, Lucy is the last person who'd ever say something so sickly-sweet.)

Unfortunately, the quote -- and its Schulz attribution -- continues to pop up in legitimate news sources, including (as just one example) no less than

the Washington Post.

Intriguingly, we've no idea where this one started, or why. Diligent research by our crack team of 5CP historians has traced the quote back to a

1999 citation in the Courier-Mail newspaper of Queensland, Australia, where it's attributed to Lucy. Book appearances seem to have started with Janet

Dailey's 2002 novel, The Only Thing Better Than Chocolate, which definitely hastened the subsequent spread. We discussed this issue with the

Charles M. Schulz Museum's Lisa Monhoff, mentioned above, who -- aside from verifying the false citations -- also couldn't suggest an origin. So the

quote clearly dates prior to 1999, given that the Courier-Mail lifted it from somewhere else (unspecified), but we've thus far been unable to source

it.

But the core fact remains: The claim that Schulz said this, either during some interview or somewhere in the Peanuts strips, is patently false.

And while we're on the subject of false attributions...

"Some day, we will all die Snoopy"

This actually is a "conversation" between Charlie Brown and Snoopy, which is the first clue that it's bogus ... because Snoopy doesn't

"talk" to people! Starting in early 2013, this two-line exchange began to circulate on a doctored version of the classic Schulz illustration of Charlie Brown and Snoopy

sitting at the edge of a dock, their backs to the camera (so to speak), and looking out at a lake. Among other uses, this image is on the back cover of

the book 50 Years of Happiness: A Tribute to Charles M. Schulz (with no dialog).

Somebody added two word balloons -- clearly not Schulz's lettering style! -- so that Charlie Brown says "Some day, we will all die Snoopy."

And then Snoopy replies (!), "True, but on all the other days, we will not."

Snoopy's "speaking" aside, the few times Schulz touched on the subject of death, he did so with humor, not fortune-cookie sermonizing. (In one droll

example, with Linus and Charlie Brown leaning on the "wall of contemplation," Linus asks "When you die, are you ever allowed to come back?" Charlie Brown

replies, "Only if you had your hand stamped.")

Alas, as with the "chocolate" quote above, people like to think this also "sounds" like Schulz ... and this doctored image is all over the Internet

now, particularly via Pinterest. (And we're not showing it here, because we don't wish to further fuel its spread!)

"Only in math problems can you buy 60 cantaloupes and no one asks what the hell is wrong with you."

Come on ... seriously?

Schulz never, ever would have used the word "hell" in a Peanuts strip. And yet this quote also is falsely attributed to him and Peanuts.

This one seems to have started in early 2014, in a single panel extracted from a daily Peanuts strip, of Sally sitting at her school desk and

looking at a piece of paper. Somebody doctored her word balloon -- again, clearly not Schulz's lettering style -- with the quote above. Granted, it's

a droll sentiment, but it didn't come from Schulz.

The amusing part is that some text versions of this quote -- with no cartoon panel -- appear as "Only in math problems can you buy 60 cantaloupes

and no one asks what ... is wrong with you," as if removing "the hell" makes it more legit. Which it still isn't.

All three of these quotes, usually minus any artwork, also appear on countless circulated lists of "Charles M. Schulz Quotes," all of which have

many legitimate Schulz and Peanuts quotes, mixed with bogus interlopers. Needless to say, most casual readers couldn't begin to distinguish the

diamonds from the lumps of coal.

More's the pity...

The love of friends and family is more important than anything else

I've lost track of the number of times this has landed in my e-mail box ... frequently passed along

by well-meaning Peanuts fans, some of whom are quite surprised when I gently point out that theyre helping

spread a hoax.

So let's be precise: This is an Internet legend, and it's spreading faster than it can be contained. More's the pity.

Well-meaning friends often send this to each other, and Peanuts fans are particularly vulnerable, because

their friends think they'll find it especially sweet.

It's often headed Charles Schultz [sic] Philosophy, and usually reads something like this:

You don't actually have to take the quiz. Just read this straight through and you'll get the point.

It is trying to make an awesome point!

Here's the first quiz:

1. Name the five wealthiest people in the world.

2. Name the last five Heisman trophy winners.

3. Name the last five winners of the Miss America contest.

4. Name 10 people who have won the Nobel or Pulitzer Prize.

5. Name the last half dozen Academy Award winners for best actor and actress.

6. Name the last decade's worth of World Series winners.

The facts are, none of us remembers the headliners of yesterday. These are no second-rate achievers.

They are the best in their fields. But the applause dies. Awards tarnish. Achievements are forgotten.

Accolades and certificates are buried with their owners.

Here's another quiz. See how you do on this one:

1. List a few teachers who aided your journey through school.

2. Name three friends who have helped you through a difficult time.

3. Name five people who have taught you something worthwhile.

4. Think of a few people who have made you feel appreciated and special.

5. Think of five people you enjoy spending time with.

6. Name half a dozen heroes whose stories have inspired you.

Easier?

The lesson: The people who make a difference in your life are not the ones with the most credentials,

the most money, or the most awards. They are the ones that care.

Don't worry about the world coming to an end today ... It's already tomorrow in Australia.

And the whole thing is credited to Charles Schulz.

Only one problem. He never wrote it or said it, and certainly never used it in a Peanuts comic

strip ... despite the fact that this quiz often arrives embellished with Peanuts artwork.

But don't take my word for it: You can read the entire debunking entry at the Internet's best source

for exposing such urban legends. Check it out here.

The folks at the Charles M. Schulz Museum have said, "We [hear about] this about once a month. Though

this saying/quiz is often attributed to Charles Schulz, he in fact made no such statement."

Part of the familiarity is understandable: The final line -- "Don't worry about the world coming to

an end today ... It's already tomorrow in Australia" -- that often appears at the end of the quiz did come

from Schulz's pen, in the Peanuts strip originally published on June 13, 1980.

Nobody knows who the real creator of this quiz is, but it has circulated on the Internet since at least 2000.

At some point, someone added Schulz's "tomorrow in Australia" line, which evidently misled a subsequent reader

into believing that Schulz had authored the quiz itself.

But he didn't.

So even if you like the soggy sentimentality -- and, granted, it's a warm and fuzzy thought -- please

don't make the situation worse by telling anybody else that Schulz had anything to do with it.

Gray areas resulting from the animated TV specials

These fuel many discussions, and some have led to arguments. Before we go any further, though, it's

important to realize that Schulz always drew a line in the sand that separated his newspaper strip from

any other incarnation of the Peanuts gang. The newspaper strip, he insisted, was what counted; everything

else was ... something else.

So it could be theorized that some of these alternate Peanuts universe facts could be true, and that Schulz

simply never got around to exploiting them in the strip.

Or maybe he never intended to; we'll never know.

But the best way to consider such issues is the same way Sherlockians distinguish Arthur Conan Doyle's

60 official Sherlock Holmes stories and short novels -- as actually published by Dr. Watson, of course -- from

the thousands of other stories that have followed during the past century, generated by hundreds of other

writers. The canonical 60 count; the others are (ahem) fictitious.

So, in the Peanuts world, the newspaper strips count; the rest ... are something else.

Charlie Brown plants a wet one on Heather

The Little Red-Haired Girl's identity

She's never been named, and she's never been shown ... although we did see her silhouette once,

when Snoopy danced with her in the daily strip originally published May 25, 1998.

On TV, however, it's true the Little Red-Haired Girl popped up in the animated special It's Your

First Kiss, Charlie Brown -- and therefore in the picture-book adapted from that show -- and was given

the named Heather. But Schulz did not regard her as the true Little Red-Haired Girl, just as Charlie Brown's

having successfully place-kicked a football in another TV special was not to be regarded as a comparative

truth in the strip.

No, the actual little red-haired girl -- like the Head Beagle, or the Great Pumpkin, or Linus' Miss

Othmar -- never was drawn, and with malice aforethought.

That way, we all got to imagine such characters to be whatever we'd like ... safe in the knowledge

that no visualization would be better, or different, than any other.

But...

There is strong evidence to suggest that Schulz did, at least, favor the name Heather.

In an interview published in the February 1968 issue of Womans Day magazine, timed to coincide with

the debut of the animated TV special He's Your Dog, Charlie Brown -- years before It's Your

First Kiss, Charlie Brown came along in 1977 -- we read the following:

Mr. Schulz is thoughtful about language. When Womans Day visited him, he had just settled on a name

for the little red-haired girl who is the object of Charlie Brown's affections.

She would be Heather, he had decided, after a little girl he had met while signing autographs for a group of children.

"I think that's a good name for her, don't you?"

So while Schulz never got around to using that name in his newspaper strip, he clearly

thought about it ... at least for awhile.

June 18, 1989

Snoopy's siblings

How many siblings does Snoopy have? Five ... or seven?

In the order that they appeared in the strip, we met Spike, Belle, Marbles, "Ugly" Olaf and Andy.

The 1991 TV special Snoopy's Reunion also mentions Molly and Rover, but they are not to be

confused with those found in the "real" world of the newspaper strip.

It is significant, though, that Schulz once drew a Sunday strip (June 18, 1989) with Snoopy's father

receiving a card signed by all eight of his offspring ... but we never officially met the other two.

That same TV special named Snoopy's mother, as well -- Missy -- but, again, although Snoopy's mother

does pop up in one daily strip (July 26, 1996), she's not identified by name.

Last names

The belief persists that most of the Peanuts characters don't have last names, when in fact we know

quite a few: Charlie and Sally Brown, of course; also Lucy, Linus and Rerun Van Pelt; and Patricia

"Peppermint Patty" Reichardt.

When 5 and his twin sisters, 3 and 4, were introduced, their last name was given as 95472 (the family's Zip code).

With respect to more obscure characters, we know of Charlotte Braun, baseball player Jose Peterson,

tennis players Molly Volley and Crybaby Boobie, Harold Angel, Tapioca Pudding, Royanne Hobbs and Joe Agate.

And here's a clever one: In the April 4, 1953, daily strip, Patty calls Violet by her full name of Violet

Gray ... a delightful verbal gag.

Thanks to the animated special You're in the Super Bowl, Charlie Brown, people can cite two others:

Marcie and Franklin are given the last names of Johnson and Armstrong, respectively. But these latter two never

were used in the newspaper strip, so we can't be certain that they're correct.

Did I miss any?

If you've encountered other Peanuts rumors, by all means pass 'em along. If they seem to be gaining traction,

I'll happily add them to this list (properly debunked, of course!).

Remember ... accuracy is our goal!

Some colleagues of mine here at NBC are trying to remember the name of the Peanuts character who walked around with a cloud over his head (not Pigpen with the dust cloud).

I called the Peanuts Research Center/Museum, and they couldn't give me the answer. But they gave me your contact information.

Can you help answer this question?

Many thanks.

Let us be absolutely clear on one point: Lisa most certainly did answer his question,

and in fact she gave him the same information I supplied. She was not amused when I forwarded

a copy of my response, particularly since this gentleman apparently took my word over

hers ... despite the fact that we both said the same thing, and she said it first.

Sexism ... becomes tiresome.

More to the point, though, this illustrates a phenomenon that I've confronted many

times over the years, in my unofficial capacity as cheerful, tireless researcher

of All Things Peanuts for people resourceful enough to contact me: the occasional refusal

to accept the response of an authoritative source, if it conflicts with one's (invariably imperfect) memory.

I mean, really, if you have a Peanuts-related question, why would you not believe an

answer supplied by the Charles M. Schulz Museum?

People can be funny. They get these ideas into their heads, and it's darn near impossible

to shake 'em loose. Doesn't matter how hard you try, how persuasively you present the dissenting

viewpoint, or the possible multitude of facts to support the actual, correct answer.

They'll continue to believe themselves correct despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

And, in fairness, the Internet has worsened this situation. Time was, a bad idea or blindingly

incorrect fact got no further than its sole point of publication. These days, such things travel

the world -- via the Web -- and propagate like fruit flies. Careless research doesn't help; a

credulous scholar easily could find several dozen sources for the same bad information ... not

realizing that every one of them merely repeated the original error, thanks to those always-busy

'bots that scoop up and distribute everything on the Web.

This, by the way, is my primary objection to a site such as Wikipedia: It's not authenticated.

Yes, some of the listings are written by experts in their field, who care deeply about accuracy.

On the other hand, many listings are contributed by well-meaning fans, who aren't always as accurate

as they'd like to believe.

And there's nothing more aggravating, when I deal with a questioner, than somebody who argues

with my response and cites a Wikipedia entry -- or something similar -- as evidence of my supposed "ignorance."

The world of Peanuts, like any other specialized field, has its share of rumors, misunderstandings

and just plain hoaxes (not too many of the latter, fortunately). Some of them predate the Internet;

others have been created and spread by the Internet. I've fielded some of them repeatedly;

so have Lisa and other highly visible Peanuts authorities such as friend and fellow PCC member Scott McGuire,

who gets the attention thanks to his highly informative Peanuts TV, film, video and book-oriented Web site.

(Check it out here.)

The note above prompted me to check in with Lisa and Scott, to gather the best -- and most

irritatingly frequent -- Peanuts rumors, misunderstandings and hoaxes. You may have seen one

or more of these. You may even believe some ... although I hope your opinion changes by the end of this article.

Mostly, though, I hope you don't spread them. The Internet becomes a scarier place when bad

information crowds out good information. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to help

stem the flow of falsehood. Stand up for the integrity of Charles Schulz's vision!

So then: to the issues at hand.

Misconceptions

Charlie Brown is bald.

This one circulates a lot, although I've rarely responded to a direct question from

somebody wanting to know one way or the other. It's just a common and patently false assumption,

based on the way Charlie Brown is drawn. He's most certainly not bald; he's just very, very, very,

very blond ... what my parents would have called a tow-head (a phrase, come to think of it,

that I don't hear much any more). Charlie Brown's hair is so fine that it simply doesn't show up

that clearly, hence we see only the occasional strand.

Confirmation for this information was given by no less than Charles Schulz himself, during a December 18,

1990, interview with Terry Gross on National Public Radio's Fresh Air:

I don't think of it as not having hair. I think of it as being hair that is so blond that ... it's

not seen very clearly, that's all.

He repeated this information a few years later, during an interview on NPR's Morning Edition:

Well, he's got hair, it's just so light you don't notice it. I always resent it when people say he's

bald. He's not bald. The old character Henry was bald. But Charlie Brown has a little hair. His dad is a barber,

as my dad was. He must have had hair someplace up there.

The issue became a bit confused in the wake of the 1975 TV special, You're a Good Sport, Charlie Brown,

when upon winning the motocross competition ol' Chuck received a prize of ... five free haircuts.

"But my dad's a barber," Charlie Brown protested, "and besides, I don't have much hair to cut!"

No problem there; it simply means that Charlie Brown's hair is mostly short, crew-cut fashion,

except for a few stray long hairs, and we always see the latter.

The Great Pumpkin lives!

Scott has gotten this question more than the rest of us, because of his Web site's focus.

For some rather peculiar reason, lots of people believe that when It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown

first showed on TV -- but only the first time -- it included a scene that actually revealed the Great Pumpkin

(sometimes thought to have been peering in a window of Linus and Lucy's house). As this rumor goes, the scene

in question was deleted after that one and only airing.

Oh, puh-leaze!

No doubt such folks misremember the fact that Linus does indeed see a shadowy figure rising from the pumpkin

patch ... but, as most of us know, that "mysterious" figure turns out to be Snoopy.

I'm sure no avid Peanuts fan would be suckered by this one; we all know that the Great Pumpkin,

like the Little Red-Haired Girl, is one of the imaginary icons that Schulz made a point of never showing

in his strip. Given the degree to which Schulz was involved in that TV special -- only the third one

created -- he most certainly never would have okayed actually revealing the Great Pumpkin, and nobody

could have made such a decision against his approval.

Besides ... what in the world would the Great Pumpkin have looked like? I mean, seriously!

And yet people swear that they saw just such a scene, that one time, and they'll refuse to take our

steadfast word that they're mistaken.

Go figure.

April 26, 1958

Charlie Brown's baseball team never won a game.

Folks take for granted -- mainly because Charlie Brown himself reinforces the notion -- that his

baseball team remained win-less every season. While ample evidence exists that things go pretty badly

("We always seem to lose the first game of the season and the last game of the season ... and all the stupid

games in between!"), in point of fact ol' Chuck's team has won a few.

A few notable newspaper strip examples:

4/26/58: Just prior to the first game of the season, Charlie Brown winds up home in bed, feeling sick.

Lucy leads the gang into his bedroom later that day, and triumphantly proclaims, "We didn't do anything

you told us! In fact, we didn't even miss you!" And, as a result, the team wins the game.

6/10/65: Having (as usual) been shipped off to camp for the summer, Charlie Brown receives a letter

from Linus, which says, among other things, "I suppose you are worried about your baseball team. Well, don't

worry ... we're doing fine ... in fact, yesterday we won the first game we've won all season!"

8/5/66: After getting hit on the head with a line drive -- a few days earlier, on 8/2 -- and being forced

to spend the rest of the game on the bench, ol' Chuck's team triumphs again. "We won, Charlie Brown!" Lucy shouts.

"We won the game!"

8/16/68: Thrown into a tizzy when he notices the Little Red-Haired Girl watching the game from the stands,

Charlie Brown gets the shakes so badly that he cannot pitch the game. Relief pitcher Linus takes over, and the

team wins again.

4/22-23/69: When Peppermint Patty and Franklin both finds themselves unable to field an entire team,

they reluctantly tell Charlie Brown that his team has won by forfeit ... both times. Alas, the two-game

winning streak ends the next day, when the other team (we don't know whose) shows up.

4/9/73: When the opposing team has trouble pitching to Rerun because of his small size, the little guy

walks in the winning run, and Linus triumphantly shouts, "We won! We won, Charlie Brown!" Alas, the Little League

president eventually takes the game away because of gambling: Rerun, ever the loyal player, bet Snoopy

a nickel that his team would win.

You may have noticed, by now, that most of these victories took place in Charlie Brown's absence ... but it's

equally untrue to assume that he never personally brought his own team to victory.

Consider, most famously...

3/30/93: With Royanne Hobbs pitching against him, Charlie Brown hits his first-ever home run (in the ninth inning)

and wins the game.

6/29/93: Once again facing Royanne Hobbs, Charlie Brown hits another home run, and brings his team to victory again.

It's true that both these home runs later prove to be bittersweet victories ... but ol' Chuck really doesn't care!

May 23, 1954

Adults never appeared in the strip.

People who still believe this one just aren't reading the strip very carefully, and I hope that Fantagraphics'

Complete Peanuts anthologies may, finally, banish this misconception once and for all.

And, as you'll also discover, dealing with this question also takes care of a second, related mistaken

assumption: Adults in Peanuts have spoken actual words. Believing otherwise is a result of the animated TV

specials, where adults mostly are limited to those hilarious waah-waah outbursts. (But not exclusively,

so let's not start that rumor, either. Adults do speak actual dialogue in some of the animated shows.)

September 18, 1966

Charlie Brown's mother makes an off-camera appearance in the 11/7/50 strip, when she calls him by name.

Similarly, Charlie Brown's father makes an off-camera appearance in the 6/20/93 Sunday strip, when he

plays with Snoopy and talks to him in no fewer than eight word-balloons. So we also have irrefutable proof

that ol' Chuck is growing up in a happy, two-parent household.

In the 10/17/54 Sunday strip, Charlie Brown, attempting to attain the same level of security as Linus,

hustles into a store to purchase one yard of outing flannel ("And DONT LAUGH!!," he tells the clerk).

Look closely, and you'll see the clerk's left hand, complete with wedding band.

The best early use of almost-wholly-there adults, however, comes in four consecutive Sunday strips involving

Lucy's participation in a golf tournament, with Charlie Brown at her side as sort of a one-man cheering squad.

Numerous adults appear in close-up, from the waist down, in a few panels. In other panels, you can see groups

of adults in the cheering gallery, although their faces remain obscured.

Schulz also used Snoopy in his infantry beagle mode to commemorate Memorial Day and Veterans Day.

The 5/31/98 Sunday strip, a huge single panel, placed the comic strip beagle against a background photograph

of soldiers designed to honor the anniversary of D-Day. Later the same year, Schulz went one better than his

usual acknowledgment of war-era cartoonist Bill Mauldin, in whose honor Snoopy usually quaffs a root beer

each November 11. In the 11/11/98 daily strip, Snoopy actually meets Mauldin's Willie and Joe, the comic

strip soldiers who conveyed the weary loneliness of WWII life for an entire generation. They're even drawn

in Mauldin's style.

So: Plenty of adults. (Back in the early days, anyway.)

Joe Btfsplk

The Peanuts character who walked around with a cloud over his head ... but who isn't Pigpen.

Yes, from the letter above. (What, you thought I wouldn't tell you?)

This is a funny one, which has been gathering steam for the past several years ... funny in the sense

that I can't imagine why, how or where the rumor could have started.

For the record, then, there's no such character in Peanuts.

It's a persistent rumor, but wholly unfounded. I suspect bad memory: Folks are conflating Pig Pen -- with

his ubiquitous dust cloud -- with an actual character from Al Capp's Li'l Abner, who walked around with a

constant raincloud over his head. That character's name was Joe Btfsplk, and you can read about him

here.

You'll also note the few panels above, taken from Li'l Abner, which show this individual. I hope you'll

agree that he doesn't look a thing like any character who'd appear in Peanuts!

Charles Schulz didn't draw all the Peanuts strips, or had helpers/associates/background artists/etc.

Okay, this one's just insulting.

And completely false.

Of all the thoughtless and silly questions that sometimes pop up, this has to be the worst. How can

you examine any single Peanuts strip and not know, without question, that they always were rendered by the same hand?

For the record, Charles Schulz was -- and always was -- the only person to draw, write and

letter his beloved newspaper comic strip. While it is true that other daily strips have been (are) drawn

and/or written by consortiums overseen by the strip's creator, this never was the case with Peanuts.

So Schulz gave us a total of 17,897 Peanuts newspaper strips: 15,391 daily strips and 2,506 Sundays.

This takes into account leap years, the fact that Sunday strips did not begin until January 1952, and the

single vacation that he took, from November 27 through December 31, 1997 (inclusive).

That already impressive number does not include the hundreds of Peanuts spot panels Schulz also

did for gift books such as Happiness is a Warm Puppy, or his numerous illustrations for magazine

covers and interior articles. He kept busy.

To a degree, the belief that other hands became involved in the newspaper strip has been enhanced by

a few recent interviews given by comic artist Al Plastino, who claims -- in Alter Ego #59, for example -- that

he did Snoopy for a year and a half, in case Charles Schulz died after heart bypass surgery. Several examples

of Plastino's potential Peanuts strips have accompanied these interviews, but it's important to realize

that none of them ever was used in an official capacity.

Incidentally, Plastino's involvement wasn't a function of Schulz's health; Plastino actually was

brought in during a time when Schulz and his syndicate were arguing over contract details, and some

syndicate wonk thought he might gain better leverage if he, um, suggested that they could easily hire

somebody else to produce the strip. (Can you imagine?) Fortunately, saner heads prevailed, and the syndicate

managed to keep Schulz happy ... and that was the end of Plastino's potential involvement with Peanuts.

It is true, on the other hand, that several other unsung individuals handled the writing and artwork

chores when the Peanuts gang appeared in Dell and Gold Key comic books during the late 1950s and early 1960s.

For full details,

check out this article.

Schulz always made it plain that the newspaper strip would retire with him, and it did.

(And for the record, the strips still appearing in newspapers are older reprints ... not new

strips done by somebody else!)

Now that he is no longer with us, nobody else will take over. And that is absolutely as it should be.

March 13, 1978

Peppermint Patty and Marcie are gay

First of all, take a deep breath, and proceed with an open mind.

Readers are absolutely entitled to draw every possible comfort from their artform of choice,

whether books, plays, movies or newspaper comic strips. It is not my intention to puncture any

joyous bubbles; the commentary here is aimed mostly at the more militant individuals who insist

on taking the "truth" of this relationship for granted.

People can believe what they want ... but it's important to recognize that Schulz intended

no such reading of Peppermint Patty and Marcie ... or, for that matter, any other character in the Peanuts world.

Consider this portion of Gary Groth's lengthy 1997 interview with Schulz, reprinted in the

book Charles M. Schulz Conversations:

Groth: You skirt sexuality per se and deal with a much more romanticized or idealized version of love:

Charlie Brown and the red-haired girl and his unrequited love for her, Peppermint Patty's interest in

Charlie Brown is oblique and touching, Lucy's unrequited love for Schroeder, etc., but you don't deal

directly with sexuality. Since the strip is one of the most personal ever done, and sexuality is such

an important part of one's life, I was wondering if you ever felt like you wanted to do that but couldn't,

because of the newspaper strip format and the restrictions of the newspaper audience.

Schulz: Well, in the first place, these are just little kids. That really puts a lid on it right there.

To Schulz, then, this was a non-issue.

Those who choose to read a gay relationship between Peppermint Patty and Marcie will point to the former's

butch behavior, and the latter's fondness for calling her friend Sir. But Peppermint Patty was designed, when

she debuted in the 1960s, as what then was known as a sports-oriented tomboy ... and there's a chasm between

tomboy and butch. And Marcie repeatedly said Sir because she mixed up her pronouns -- like Sally mangled the English

language -- and (later) because it annoyed Peppermint Patty ... and Marcie knew it. (And also because it was funny,

and Schulz knew it.)

July 21, 1979

Perhaps more crucial to this argument, as Groth mentioned above, is the fact that both Peppermint Patty and Marcie

have competitive crushes on Charlie Brown. Both dream of kissing him. Both have done so.

August 18, 1982

In the second Peanuts stage play, Snoopy!, an entire song -- "Poor Sweet Baby" -- was constructed around

Peppermint Patty's love for Charlie Brown.

May 28, 1973

For what it's worth, Peppermint Patty also dated Pig Pen briefly, in early 1980; they attended a dance together,

and Peppermint Patty came home quite smitten. But it didn't last, and she sooned resumed pining for Charlie Brown.

So, by all means, believe what you so desire ... but if you like the thought of Peppermint Patty and Marcie

being a couple, the newspaper strip evidence simply doesn't support that theory.

Hoaxes and pernicious fakes

The Snoopy IRS strip

No less a journalist than financial columnist Stephen Moore, writing for National Review Online, began

an April 15, 2003, column with the following paragraph:

Many years ago I framed a classic Peanuts cartoon on the wall of my office. It shows Snoopy sitting

on top of his dog house pecking away at his typewriter. The message he writes is,

Dear IRS: Please take me off your mailing list!

Only one problem, Steve: There's no such classic Peanuts strip!

The, ah, anomaly in question began life as Charles Schulz's June 19, 1997, Peanuts cartoon,

with Snoopy typing out the latest exploits of Andy and Olaf. Somebody -- possibly even a legitimate

editorial cartoonist -- re-lettered the strip so that Snoopy is typing, "Dear IRS, I am writing to you

to cancel my subscription. Please remove my name from your mailing list."

At the time, and in whatever original publication produced this item -- if it was, indeed, a legitimate

source -- Schulz may have been thanked and credited, as is standard with editorial cartoons. At this point,

though, that important little detail is long behind us.

The new words aren't even a close approximation of Schulz's distinctive lettering style. Despite this,

the legend has become famous enough that I frequently get requests from people who want to know which book

contains this strip.

(And no, I've no intention of reprinting the bogus strip here, because I don't wish to help it propogate further.)

Chances are, we'll never eradicate this menace now. But it won't be for lack of trying...

Charlie Brown, archery cheater

Same question, different particulars: People want to know where they can find the "hilarious strip" that

shows Charlie Brown shooting arrows into a fence; he then draws circles around one of the buried arrows

so that it appears as though he has achieved a perfect bull's-eye.

Same answer: No such strip exists.

When the print version of this article debuted in the Summer 2007 issue of the quarterly Peanuts Collector

Club newsletter, I mentioned at the time that this hoax was a little harder to fathom, because we never had seen

a faked strip that might explain why people keep remembering it.

It's true that Charlie Brown was quite the scamp in the strip's early years, displaying characteristics

we'd more likely expect from Dennis the Menace or Calvin, of Calvin & Hobbes. We wouldn't be surprised to see

either of those characters pull such a stunt ... although, as far as we've been able to determine, they never did.

Federal Trade Commission Chairman Timothy J. Muris referenced this anomaly, in a speech he gave June 11, 2002,

on the FTC's new privacy agenda (and noted in a subsequent press release):

In concluding his remarks, the Chairman described one of his "favorite Peanuts cartoons," in which Charlie Brown

first shoots an arrow at a fence and then draws a target around it, ensuring he gets a bull's-eye.

"It might have worked for Charlie Brown, but not for us," Muris said, regarding implementation of the FTC's

Privacy Agenda goals. "We have our targets in place. We are sending out many arrows. Our law enforcement and

related initiatives indicate that our aim is darned good."

So ... what are Muris and the others remembering?

Thanks to PCC member Michael Ingrassia, we now have an answer.

A syndicated comic panel called Brother Juniper featured that gag, and it also became

the cover of one of the pocket book reprints of Brother Juniper cartoons. As with Pig Pen and Joe Btfsplk, it

seems that folks are conflating two different characters. It almost makes sense, since Brother Juniper was

drawn in a way that suggests he didn't have much hair, as people frequently assume is the case with

Charlie Brown (see above).

You can find the cover for Brother Juniper Strikes Again by Justin McCarthy

right here.

"All you need is love ... but a little chocolate now and then doesn't hurt."

The quote above, which has become incredibly pervasive -- turning up on samplers, posters and countless versions of desktop art -- most frequently

is attributed to Schulz, and sometimes to Lucy. Such claims notwithstanding, Schulz never said any such thing, nor did any character in any Peanuts

strip say anything remotely approaching this phrase. (On top of which, Lucy is the last person who'd ever say something so sickly-sweet.)

Unfortunately, the quote -- and its Schulz attribution -- continues to pop up in legitimate news sources, including (as just one example) no less than

the Washington Post.

Intriguingly, we've no idea where this one started, or why. Diligent research by our crack team of 5CP historians has traced the quote back to a

1999 citation in the Courier-Mail newspaper of Queensland, Australia, where it's attributed to Lucy. Book appearances seem to have started with Janet

Dailey's 2002 novel, The Only Thing Better Than Chocolate, which definitely hastened the subsequent spread. We discussed this issue with the

Charles M. Schulz Museum's Lisa Monhoff, mentioned above, who -- aside from verifying the false citations -- also couldn't suggest an origin. So the

quote clearly dates prior to 1999, given that the Courier-Mail lifted it from somewhere else (unspecified), but we've thus far been unable to source

it.

But the core fact remains: The claim that Schulz said this, either during some interview or somewhere in the Peanuts strips, is patently false.

And while we're on the subject of false attributions...

"Some day, we will all die Snoopy"

This actually is a "conversation" between Charlie Brown and Snoopy, which is the first clue that it's bogus ... because Snoopy doesn't

"talk" to people! Starting in early 2013, this two-line exchange began to circulate on a doctored version of the classic Schulz illustration of Charlie Brown and Snoopy

sitting at the edge of a dock, their backs to the camera (so to speak), and looking out at a lake. Among other uses, this image is on the back cover of

the book 50 Years of Happiness: A Tribute to Charles M. Schulz (with no dialog).

Somebody added two word balloons -- clearly not Schulz's lettering style! -- so that Charlie Brown says "Some day, we will all die Snoopy."

And then Snoopy replies (!), "True, but on all the other days, we will not."

Snoopy's "speaking" aside, the few times Schulz touched on the subject of death, he did so with humor, not fortune-cookie sermonizing. (In one droll

example, with Linus and Charlie Brown leaning on the "wall of contemplation," Linus asks "When you die, are you ever allowed to come back?" Charlie Brown

replies, "Only if you had your hand stamped.")

Alas, as with the "chocolate" quote above, people like to think this also "sounds" like Schulz ... and this doctored image is all over the Internet

now, particularly via Pinterest. (And we're not showing it here, because we don't wish to further fuel its spread!)

"Only in math problems can you buy 60 cantaloupes and no one asks what the hell is wrong with you."

Come on ... seriously?

Schulz never, ever would have used the word "hell" in a Peanuts strip. And yet this quote also is falsely attributed to him and Peanuts.

This one seems to have started in early 2014, in a single panel extracted from a daily Peanuts strip, of Sally sitting at her school desk and

looking at a piece of paper. Somebody doctored her word balloon -- again, clearly not Schulz's lettering style -- with the quote above. Granted, it's

a droll sentiment, but it didn't come from Schulz.

The amusing part is that some text versions of this quote -- with no cartoon panel -- appear as "Only in math problems can you buy 60 cantaloupes

and no one asks what ... is wrong with you," as if removing "the hell" makes it more legit. Which it still isn't.

All three of these quotes, usually minus any artwork, also appear on countless circulated lists of "Charles M. Schulz Quotes," all of which have

many legitimate Schulz and Peanuts quotes, mixed with bogus interlopers. Needless to say, most casual readers couldn't begin to distinguish the

diamonds from the lumps of coal.

More's the pity...

The love of friends and family is more important than anything else

I've lost track of the number of times this has landed in my e-mail box ... frequently passed along

by well-meaning Peanuts fans, some of whom are quite surprised when I gently point out that theyre helping

spread a hoax.

So let's be precise: This is an Internet legend, and it's spreading faster than it can be contained. More's the pity.

Well-meaning friends often send this to each other, and Peanuts fans are particularly vulnerable, because

their friends think they'll find it especially sweet.

It's often headed Charles Schultz [sic] Philosophy, and usually reads something like this:

You don't actually have to take the quiz. Just read this straight through and you'll get the point.

It is trying to make an awesome point!

Here's the first quiz:

1. Name the five wealthiest people in the world.

2. Name the last five Heisman trophy winners.

3. Name the last five winners of the Miss America contest.

4. Name 10 people who have won the Nobel or Pulitzer Prize.

5. Name the last half dozen Academy Award winners for best actor and actress.

6. Name the last decade's worth of World Series winners.

The facts are, none of us remembers the headliners of yesterday. These are no second-rate achievers.

They are the best in their fields. But the applause dies. Awards tarnish. Achievements are forgotten.

Accolades and certificates are buried with their owners.

Here's another quiz. See how you do on this one:

1. List a few teachers who aided your journey through school.

2. Name three friends who have helped you through a difficult time.

3. Name five people who have taught you something worthwhile.

4. Think of a few people who have made you feel appreciated and special.

5. Think of five people you enjoy spending time with.

6. Name half a dozen heroes whose stories have inspired you.

Easier?

The lesson: The people who make a difference in your life are not the ones with the most credentials,

the most money, or the most awards. They are the ones that care.

Don't worry about the world coming to an end today ... It's already tomorrow in Australia.

And the whole thing is credited to Charles Schulz.

Only one problem. He never wrote it or said it, and certainly never used it in a Peanuts comic

strip ... despite the fact that this quiz often arrives embellished with Peanuts artwork.

But don't take my word for it: You can read the entire debunking entry at the Internet's best source

for exposing such urban legends. Check it out here.

The folks at the Charles M. Schulz Museum have said, "We [hear about] this about once a month. Though

this saying/quiz is often attributed to Charles Schulz, he in fact made no such statement."

Part of the familiarity is understandable: The final line -- "Don't worry about the world coming to

an end today ... It's already tomorrow in Australia" -- that often appears at the end of the quiz did come

from Schulz's pen, in the Peanuts strip originally published on June 13, 1980.

Nobody knows who the real creator of this quiz is, but it has circulated on the Internet since at least 2000.

At some point, someone added Schulz's "tomorrow in Australia" line, which evidently misled a subsequent reader

into believing that Schulz had authored the quiz itself.

But he didn't.

So even if you like the soggy sentimentality -- and, granted, it's a warm and fuzzy thought -- please

don't make the situation worse by telling anybody else that Schulz had anything to do with it.

Gray areas resulting from the animated TV specials

These fuel many discussions, and some have led to arguments. Before we go any further, though, it's

important to realize that Schulz always drew a line in the sand that separated his newspaper strip from

any other incarnation of the Peanuts gang. The newspaper strip, he insisted, was what counted; everything

else was ... something else.

So it could be theorized that some of these alternate Peanuts universe facts could be true, and that Schulz

simply never got around to exploiting them in the strip.

Or maybe he never intended to; we'll never know.

But the best way to consider such issues is the same way Sherlockians distinguish Arthur Conan Doyle's

60 official Sherlock Holmes stories and short novels -- as actually published by Dr. Watson, of course -- from

the thousands of other stories that have followed during the past century, generated by hundreds of other

writers. The canonical 60 count; the others are (ahem) fictitious.

So, in the Peanuts world, the newspaper strips count; the rest ... are something else.

Charlie Brown plants a wet one on Heather

The Little Red-Haired Girl's identity

She's never been named, and she's never been shown ... although we did see her silhouette once,

when Snoopy danced with her in the daily strip originally published May 25, 1998.

On TV, however, it's true the Little Red-Haired Girl popped up in the animated special It's Your

First Kiss, Charlie Brown -- and therefore in the picture-book adapted from that show -- and was given

the named Heather. But Schulz did not regard her as the true Little Red-Haired Girl, just as Charlie Brown's

having successfully place-kicked a football in another TV special was not to be regarded as a comparative

truth in the strip.

No, the actual little red-haired girl -- like the Head Beagle, or the Great Pumpkin, or Linus' Miss

Othmar -- never was drawn, and with malice aforethought.

That way, we all got to imagine such characters to be whatever we'd like ... safe in the knowledge

that no visualization would be better, or different, than any other.

But...

There is strong evidence to suggest that Schulz did, at least, favor the name Heather.

In an interview published in the February 1968 issue of Womans Day magazine, timed to coincide with

the debut of the animated TV special He's Your Dog, Charlie Brown -- years before It's Your

First Kiss, Charlie Brown came along in 1977 -- we read the following:

Mr. Schulz is thoughtful about language. When Womans Day visited him, he had just settled on a name

for the little red-haired girl who is the object of Charlie Brown's affections.

She would be Heather, he had decided, after a little girl he had met while signing autographs for a group of children.

"I think that's a good name for her, don't you?"

So while Schulz never got around to using that name in his newspaper strip, he clearly

thought about it ... at least for awhile.

June 18, 1989

Snoopy's siblings

How many siblings does Snoopy have? Five ... or seven?

In the order that they appeared in the strip, we met Spike, Belle, Marbles, "Ugly" Olaf and Andy.

The 1991 TV special Snoopy's Reunion also mentions Molly and Rover, but they are not to be

confused with those found in the "real" world of the newspaper strip.

It is significant, though, that Schulz once drew a Sunday strip (June 18, 1989) with Snoopy's father

receiving a card signed by all eight of his offspring ... but we never officially met the other two.

That same TV special named Snoopy's mother, as well -- Missy -- but, again, although Snoopy's mother

does pop up in one daily strip (July 26, 1996), she's not identified by name.

Last names

The belief persists that most of the Peanuts characters don't have last names, when in fact we know

quite a few: Charlie and Sally Brown, of course; also Lucy, Linus and Rerun Van Pelt; and Patricia

"Peppermint Patty" Reichardt.

When 5 and his twin sisters, 3 and 4, were introduced, their last name was given as 95472 (the family's Zip code).

With respect to more obscure characters, we know of Charlotte Braun, baseball player Jose Peterson,

tennis players Molly Volley and Crybaby Boobie, Harold Angel, Tapioca Pudding, Royanne Hobbs and Joe Agate.

And here's a clever one: In the April 4, 1953, daily strip, Patty calls Violet by her full name of Violet

Gray ... a delightful verbal gag.

Thanks to the animated special You're in the Super Bowl, Charlie Brown, people can cite two others:

Marcie and Franklin are given the last names of Johnson and Armstrong, respectively. But these latter two never

were used in the newspaper strip, so we can't be certain that they're correct.

Did I miss any?

If you've encountered other Peanuts rumors, by all means pass 'em along. If they seem to be gaining traction,

I'll happily add them to this list (properly debunked, of course!).

Remember ... accuracy is our goal!

More to the point, though, this illustrates a phenomenon that I've confronted many

times over the years, in my unofficial capacity as cheerful, tireless researcher

of All Things Peanuts for people resourceful enough to contact me: the occasional refusal

to accept the response of an authoritative source, if it conflicts with one's (invariably imperfect) memory.

I mean, really, if you have a Peanuts-related question, why would you not believe an

answer supplied by the Charles M. Schulz Museum?

People can be funny. They get these ideas into their heads, and it's darn near impossible

to shake 'em loose. Doesn't matter how hard you try, how persuasively you present the dissenting

viewpoint, or the possible multitude of facts to support the actual, correct answer.

They'll continue to believe themselves correct despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

And, in fairness, the Internet has worsened this situation. Time was, a bad idea or blindingly

incorrect fact got no further than its sole point of publication. These days, such things travel

the world -- via the Web -- and propagate like fruit flies. Careless research doesn't help; a

credulous scholar easily could find several dozen sources for the same bad information ... not

realizing that every one of them merely repeated the original error, thanks to those always-busy

'bots that scoop up and distribute everything on the Web.

This, by the way, is my primary objection to a site such as Wikipedia: It's not authenticated.

Yes, some of the listings are written by experts in their field, who care deeply about accuracy.

On the other hand, many listings are contributed by well-meaning fans, who aren't always as accurate

as they'd like to believe.

And there's nothing more aggravating, when I deal with a questioner, than somebody who argues

with my response and cites a Wikipedia entry -- or something similar -- as evidence of my supposed "ignorance."

The world of Peanuts, like any other specialized field, has its share of rumors, misunderstandings

and just plain hoaxes (not too many of the latter, fortunately). Some of them predate the Internet;

others have been created and spread by the Internet. I've fielded some of them repeatedly;

so have Lisa and other highly visible Peanuts authorities such as friend and fellow PCC member Scott McGuire,

who gets the attention thanks to his highly informative Peanuts TV, film, video and book-oriented Web site.

(Check it out here.)

The note above prompted me to check in with Lisa and Scott, to gather the best -- and most

irritatingly frequent -- Peanuts rumors, misunderstandings and hoaxes. You may have seen one

or more of these. You may even believe some ... although I hope your opinion changes by the end of this article.

Mostly, though, I hope you don't spread them. The Internet becomes a scarier place when bad

information crowds out good information. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to help

stem the flow of falsehood. Stand up for the integrity of Charles Schulz's vision!

So then: to the issues at hand.

Misconceptions

Charlie Brown is bald.

This one circulates a lot, although I've rarely responded to a direct question from

somebody wanting to know one way or the other. It's just a common and patently false assumption,

based on the way Charlie Brown is drawn. He's most certainly not bald; he's just very, very, very,

very blond ... what my parents would have called a tow-head (a phrase, come to think of it,

that I don't hear much any more). Charlie Brown's hair is so fine that it simply doesn't show up

that clearly, hence we see only the occasional strand.

Confirmation for this information was given by no less than Charles Schulz himself, during a December 18,

1990, interview with Terry Gross on National Public Radio's Fresh Air:

I don't think of it as not having hair. I think of it as being hair that is so blond that ... it's

not seen very clearly, that's all.

He repeated this information a few years later, during an interview on NPR's Morning Edition:

Well, he's got hair, it's just so light you don't notice it. I always resent it when people say he's